Trailblazing Regents' Professor Chronicled Computing in Communist Countries, Now Creating Cyber Curriculum

On the third floor of the Habersham Building, home of the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, sits an office that could almost be mistaken for a museum.

Inside, Regents’ Professor Seymour Goodman sits surrounded by the mementos and artifacts he collected while researching computing from around the world. Goodman visited all seven continents before coming to Georgia Tech in 2000, and despite an academic career of more than 60 years at eight R1 research institutions, he says he won’t retire until he has finished one final project.

“Here I am, maybe not for much longer, but I am determined to see the curriculum for the School of Cybersecurity and Privacy (SCP) through,” said Goodman. “Everyone here is building a career and I am dismantling one.”

The twice reappointed Regents’ Professor joined SCP when it was founded in 2020 with the goal of taking Georgia Tech’s existing Master of Science in Cybersecurity (MS Cybersecurity) and expanding it to fit the interdisciplinary scope of the new school. Additionally, Goodman is determined to create a cybersecurity undergraduate thread in the College of Computing.

However, it is a long and difficult road to get any course or curriculum approved. Goodman must find the common ground between computing, engineering, and policy topics along with their students and faculty. Over the next two years, the school anticipates creating more than a dozen new courses and at least one additional undergraduate thread.

“We must serve what we expect to be great demand among the large and growing undergraduate and master’s student populations in the College of Computing and elsewhere in Georgia Tech,” Goodman said. “This is particularly challenging since we see the school and cybersecurity in an interdisciplinary light.”

There is no blueprint for a cybersecurity school like this, but this isn’t Goodman’s first time spearheading a one-of-a-kind project. In fact, he has built his entire career around it.

In the early 1970’s, researchers in the United States had little to no knowledge of the work being done by computer scientists in communist countries and many assumed there was nothing worth studying. Goodman recalled one colleague claim that computing in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was completely stifled by its authoritarian government. Goodman decided to spend the next 17 years personally studying of the development, diffusion, and absorption of computing in communist countries.

“This effort started in 1975 as an outgrowth in my interest in Soviet science and scientists who were important to my Ph.D. dissertation,” said Goodman. “Our research took us to every communist country except Albania and North Korea.”

Technically, Goodman did set foot on North Korean soil, but he doesn’t count that as an actual visit. As Goodman and his Ph.D. students traveled from country to country, they observed the progress and problems of Soviet computing. The project came to a natural conclusion when the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991, which Goodman witnessed first-hand.

“I was part of the last US National Academy of Sciences delegation hosted by the Soviet Academy of Sciences,” he said. “While we were there, we became the first to be hosted by the new Russian Academy of Sciences.”

Shortly after starting the multi-year research effort into computing, Goodman decided to start another one, but this time he and his students would study the global diffusion of the internet. Following the closure of the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) in 1990, computer scientists were at odds over how to expand and implement a similar network for the public.

The consensus at the time was that this computer network, what would become the internet, would only be available to a handful of countries by 2000. Goodman’s estimate, however, was much higher. He believed the internet would be in 60 countries by the end of the century. He was off by a factor of three.

Goodman, then a professor at Stanford University, grabbed his passport once again and traveled around the world to research a unique problem. He and his students were looking for resources that could support an internet infrastructure.

“We were looking to see if they had computers and electricity,” said Goodman. “In 1993, computing was being invested in by the U.S. Department of Defense and technology accessibility was a big deal at Stanford.”

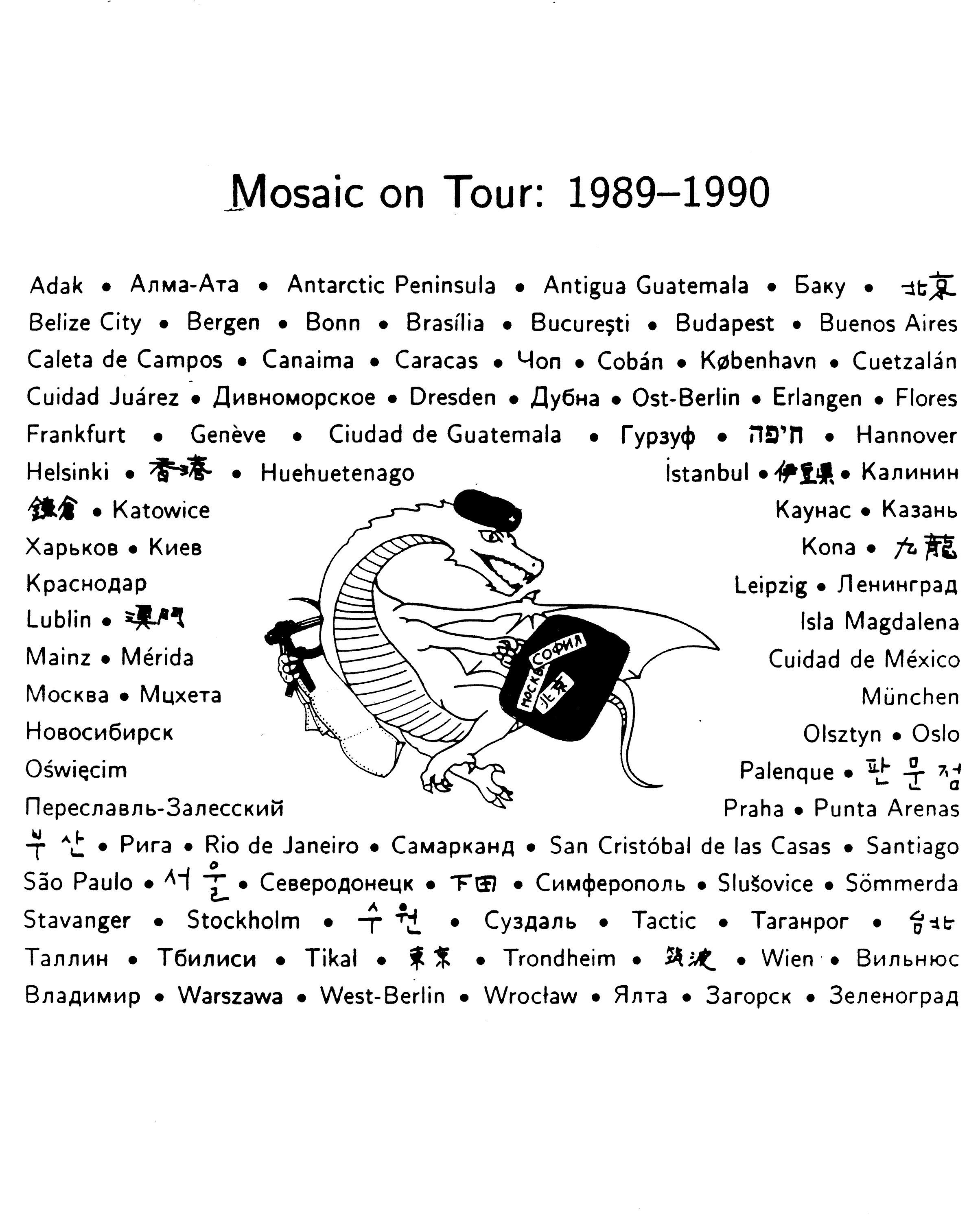

During 1989 and 1990 Goodman visited over 50 countries, specifically developing countries believed to be a lost cause for internet access by researchers at the time. In his 1994 paper, The Global Diffusion of the Internet: Patterns and Problems, Goodman argued that despite the rapidly growing number of internet users, less wealthy countries and individuals were being left behind when it came to internet accessibility.

Again, the project came to a natural end when the internet and cellular technology found its way into every country and territory on the planet by the end of the 2000’s. Their last concentrated effort focused on the continent of Africa and included efforts to bring cybersecurity to countries who were just getting extensively networked. Both projects took Goodman to over 100 countries and to all seven continents.

“I saw an early need for internet security,” said Goodman. “I was brought to the College of Computing at Georgia Tech by our first dean, Peter Freeman, in 2000 because of my background with information security and critical infrastructure.”

Today, Goodman serves jointly in the School of Cybersecurity and Privacy and Sam Nunn School of International Affairs where he studies international developments in information technologies and their related public policy issues. Throughout his career he has published over 150 papers and has served on almost every kind of committee imaginable.

But his work is far from over. Goodman has a vision for the cybersecurity curriculum at Georgia Tech that not only includes a revitalized master’s program and new undergraduate thread, but an interdisciplinary cybersecurity curriculum that can be implemented across the Institute as well.

“I believe it is our obligation as a school to get this done,” said Goodman. “This is my current and final concern with computing at Georgia Tech.”

The School of Cybersecurity and Privacy, one of five schools in the top ten ranked College of Computing, was formed in September 2020. It builds on the strong foundation and continued success of the cybersecurity research, education, and service efforts at Georgia Tech that began more than twenty years ago.

The school’s work is both interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary. Many current faculty have joint appointments with other schools in the College of Computing, as well as with the School of Computational Science and Engineering within the College of Engineering, the Scheller College of Business, the School of Public Policy, and the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, both in the Ivan Allen College of the Liberal Arts.